For decades, the Nigerian energy narrative was one of “enforced darkness” and a chronic reliance on the “generator economy”. However, by early 2026, the narrative has shifted from a lack of supply to a fundamental realignment of demand. We have reached what analysts describe as the “silicon tipping point.” For the first time in the history of the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry (NESI), the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for small-scale solar systems has dipped to ₦85–140 per kilowatt-hour (kWh), officially below the grid tariff for Band A consumers at ₦225–₦270 per kWh. While this marks a landmark for energy sovereignty, it carries a heavy fiscal warning. Recent data from Pakistan – a nation currently grappling with a chaotic solar boom – suggests that an unmanaged exodus from the national grid can simultaneously empower the individual and bankrupt the state. The choice facing Nigerian policy makers is no longer whether to embrace solar, but how to manage a market that is increasingly routing around the state to ensure its own survival. This Newsletter argues that unless Nigeria deliberately redesigns its grid and regulatory architecture to integrate, rather than resist, the solar boom, it will replicate Pakistan’s fiscal crisis and entrench a new form of energy apartheid.

The Economics of Necessity

Nigeria’s transition is not born of green ambition but raw necessity. In the last twenty-four months, the government has begun peeling back electricity subsidies in a targeted way, starting with Band A customers who enjoy the most reliable supply. In April 2024, tariffs for this small, better-served segment jumped by more than 200%, sharply reducing subsidies for Band A while leaving Bands B–E on heavily subsidised. Simultaneously, the removal of petrol subsidies and the liberalisation and subsequent steep depreciation of the naira effectively killed the “generator alternative” for SMEs, with fuel costs rising by 300%.

While local grid costs climbed, global market dynamics provided the “escape hatch.” A massive overproduction of solar modules in China, $0.25–0.35/Watt-peak (Wp) to $0.07–0.12/Wp over 18 months spanning 2024 into early 2025, turned Nigeria into a prime destination for cheap PV technology. At current market rates, a Nigerian business can generate its own power for an unsubsidised cost of ₦85 to ₦140 per kWh. For any rational economic actor, the choice is no longer an ideological one; it is an act of fiscal arbitrage. The grid has become a luxury good that delivers an inferior service, while solar has transitioned from a niche “backup” to a primary source of industrial and residential power.

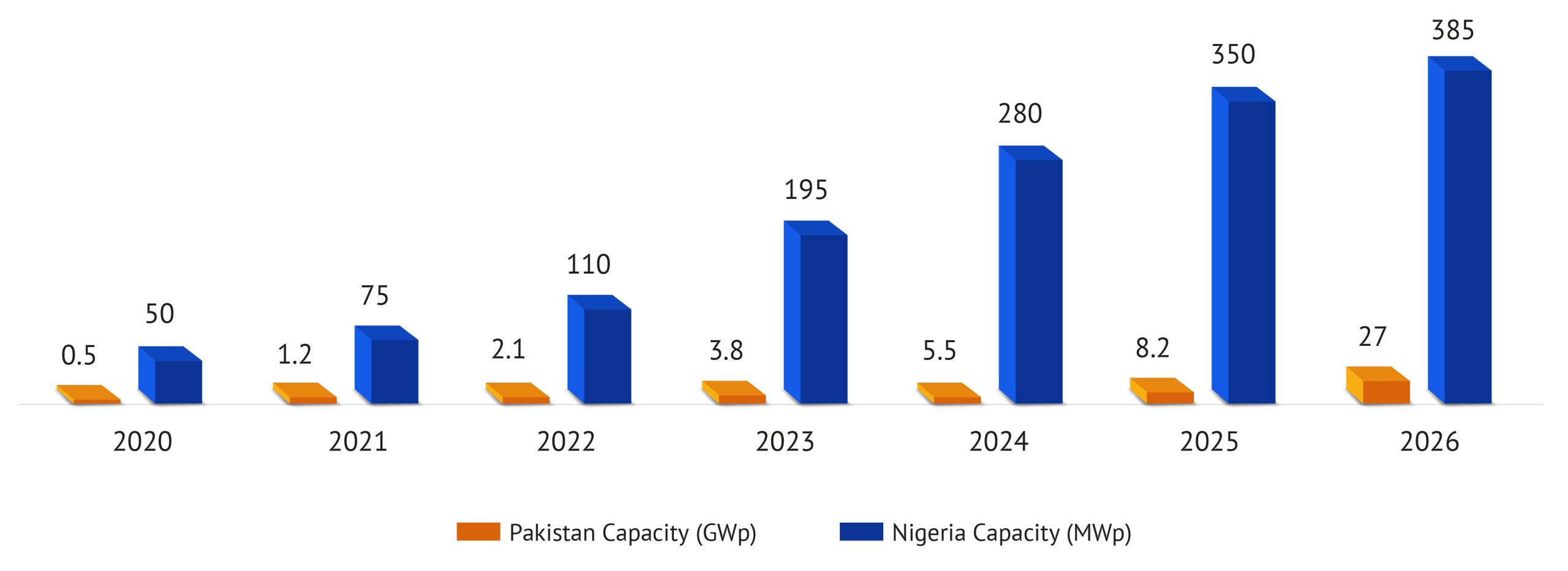

Figure 1: Solar Capacity Growth (Pakistan vs. Nigeria, 2020-2026)

Source: TransitionZero, NERC/REA reports

Pakistan’s Solar Paradox: Bottom-Up Success, System-Level Strain

To understand the systemic risk Nigeria now faces, we must look at the “Solar Rush” in Pakistan, which began under similar circumstances to Nigeria’s boom. Pakistan’s rooftop solar surge shows how a poorly managed transition can deliver household‑level relief while pushing the national grid toward insolvency; its experience is a cautionary template for Nigeria’s next decade. Chronic blackouts, epitomised by the January 2023 nationwide plunge costing PKR100 billion ($359 million USD), rendered the grid untenable. An IMF-mandated fiscal consolidation exercise saw electricity tariffs spike 155% over three years, diesel became unaffordable and Chinese panels flooded markets at historic low prices. Consumers responded organically: peri-urban families installed solar systems on rooftops for fans and refrigerators; farmers installed “jury-rigged” tractor-battery arrays for irrigation; shopkeepers shared daytime surplus informally. Capacity quadrupled to 4.1GW by late 2024 and to over 6GW in early 2026, predominantly distributed across rooftops rather than utility-scale installations. Crucially, most of these systems are grid‑tied rather than fully off‑grid: households and businesses lean on solar during the day, then fall back on the national grid at night and in low‑sun seasons. Pakistan has become one of the world’s largest importers of Chinese solar panels, acquiring roughly 13GW to 15GW in 2024 alone. For context, this is more than double the total operational capacity of the Nigerian national grid of 5,400 MW as at February 2026.

The success of the Pakistani private sector in achieving energy independence, however, has birthed a fiscal nightmare for the state. Pakistan is tethered to “Take-or-Pay” contracts with large-scale fossil-fuel plants, many funded through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The state remains contractually bound to pay “capacity charges” for electricity regardless of whether the grid is actually used. As the wealthiest consumers, the very revenue base upon which these payments depend, exit the grid via solar, the government is left with a widening PKR2.6-3 trillion ($9.3-10.8 billion) hole in its national accounts. This has triggered a “Utility Death Spiral” where the state hikes tariffs on the remaining, poorer customers to cover the deficit, only to incentivise more consumers to defect to solar. Grid sales fell 10% in FY2023; a mere 5% demand drop imposed PKR131 billion ($470 million USD) extra on remaining customers. Pakistan is not experiencing a clean break from the grid so much as a selective withdrawal: prosumers largely vanish from the system when solar is abundant, then return en masse at night, obliging the grid to maintain costly stand‑by capacity for increasingly acute evening demand spikes.

The Forensic Reality of Nigerian DisCo Fragility

Nigeria’s electricity distribution sector is on a significantly more precarious footing than its Pakistani counterpart was at the start of its solar boom. In Q1 2025, DisCos reported ATC&C losses of 36.8%, which is 16.3 percentage points above the regulatory target. With collection efficiency at 75.1%, these utilities are failing to capture nearly a quarter (24.9%) of billed revenue. In such a fragile ecosystem, the mass defection of “high-value” Band A customers is no longer just a financial challenge but has become a terminal threat to the industry’s solvency.

If the “productive class” continues its great exit, the DisCos will lose the cross-subsidisation that keeps the lower-income segments viable. We face the grim prospect of a hollowed-out national infrastructure where the “grid of the future” becomes a toxic pool of non-paying customers and decaying wires. Furthermore, the technical “Duck Curve” phenomenon poses a risk to grid stability. During the day, solar users stop drawing from the grid, causing demand to crater; but in the evening, they flood back onto the system, forcing the grid to maintain expensive “spinning reserves” that sit idle and unprofitable during the day. This creates an inefficient capital allocation that the Nigerian economy can ill afford. This pattern is already visible in Pakistan, where utilities report midday demand collapses followed by steep evening ramps as solar users reconnect to the grid once the sun sets. In other words, Nigeria is entering a Pakistan‑style transition from a far weaker starting point, which makes a laissez‑faire approach to solar adoption especially dangerous.

Energy Apartheid: The Social Redistribution of Darkness

The most alarming insight from the Pakistani precedent is the “inequity of the exit.” Solar remains an upfront-capital technology. Middle-class households can recover their ₦4 million investment in a 5kVA hybrid solar system within 18 months through diesel offset savings of ₦150,000-₦180,000 monthly, while urban poor and rural communities remain grid-trapped as tariffs rise. This creates a state of “Energy Apartheid,” where the elite live on silicon islands of 24/7 power, while the poor bear the total cost of a bankrupt national utility.

Nigeria is uniquely vulnerable to this social redistribution of darkness. If the government fails to intervene, we will see a widening gap between the “energy sovereign” and the “grid-dependent.” The $750 million World Bank-funded DARES programme represents a potential lifeline, but its execution must move beyond top-down rural electrification and focus on “urban equity.” Without credit facilities for small-scale solar kits for artisans and petty traders, the “silicon revolution” will remain a gated community phenomenon, further entrenching the economic divide in a nation already struggling with extreme wealth disparity. Without deliberate policy, Nigeria’s solar revolution will not just strain the grid; it will hard‑wire a two‑tier energy order.

The Constitutional Pivot: State-Led Regulatory Zones

A significant lever for Nigeria, which was largely absent in the Pakistani centralised model, is the 2023 Electricity Act. By granting states the power to regulate their own electricity markets, the Act creates a pathway for “Independent Regulatory Zones.” States like Lagos, Edo, and Ekiti can now license their own mini-grids and sub-franchisees. This decentralisation offers a unique solution to the “Death Spiral.” Instead of a total exit, these states can encourage “Sub-Franchising,” where private operators take over the management of specific DisCo feeders.

Under this model, the private operator integrates large-scale solar arrays into the local distribution network, reducing the reliance on the national transmission grid while maintaining the “utility” relationship with the customer. This “Grid-Plus” approach prevents the total financial collapse of the legacy assets by allowing private capital to “patch” the grid’s deficiencies from the bottom up. It represents a transition from a monolithic state monopoly to a polycentric energy ecosystem that can absorb the shocks of the solar transition without triggering a systemic default.

Conclusion: Engineering a Managed Energy Future

The announcement that solar has become cheaper than the grid in Nigeria is a momentous achievement for the market, but a daunting one for the state. We are witnessing a fundamental democratisation of the means of energy production. For the first time, the private sector is no longer a hostage to the inefficiencies of a central bureaucracy. However, as the Pakistani experience demonstrates, a revolution without a roadmap leads to fiscal anarchy and social division.

Nigeria’s energy future depends on our ability to transform the national grid from a monolithic supplier into a smart, integrated platform. We must move beyond “Net-Metering” and adopt a “Net-Billing” framework that ensures “prosumers” contribute to the fixed costs of the national wires. We must embrace the silence of the silicon panels, but we must ensure that this silence does not mask the fiscal collapse of our national infrastructure. The sun is shining on Nigeria; the challenge for our regulators is to ensure that its light is shared by all, and that the “great exit” of today does not lead to the dark silence of a bankrupt tomorrow.