Nigeria’s current economic reform program, initiated in May 2023, represented a necessary, albeit high-risk, “shock therapy” designed to correct deep-rooted structural distortions. For years, the Nigerian economy had been suffocated by a debilitating petrol subsidy, which cost over $10 billion annually at its peak, an arbitrage-ridden multi-tiered foreign exchange regime, and mounting public debt. The decision to immediately scrap the subsidy and float the Naira was hailed by multilateral institutions as brave, necessary, and long overdue. However, what followed in the immediate aftermath was a wave of severe economic dislocation and heightened volatility. Inflation, already high, accelerated to a three-decade peak of 34% in December 2024. Food inflation soared past 40%, transport costs tripled, and the Naira plunged 72% to an all-time low of ₦1696/$ as at 18 November 2024 before rebounding.

Two years later, the consensus is that the worst is over and the dust is beginning to settle. The critical question is no longer about the pain, but about the pay-off. Are we seeing the first tangible signs of macroeconomic stability? And if so, why is this stability so disconnected from the daily reality of 139 million Nigerians estimated to be living in poverty, and what will it take to bridge that chasm?

The Full Scope of the Reform Agenda

While the “twin reforms” of subsidy removal and FX unification grabbed the headlines, the policy shift since 2023 has, in fact, been more comprehensive, with a seemingly full-scale pivot to a market-driven economy. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), abandoning its prior heterodox interventions, embarked on an aggressive and orthodox monetary tightening cycle. Through 2024 and 2025, successive, steep hikes to the Monetary Policy Rate and the Cash Reserve Ratio were implemented, aimed at combating inflation, stabilising the Naira, and attracting foreign capital by offering some of the highest yields in emerging markets. At the same time, the CBN’s mandated recapitalisation for banks is intended to create financial institutions robust enough to underpin the government’s aspirations for a $1 trillion economy.

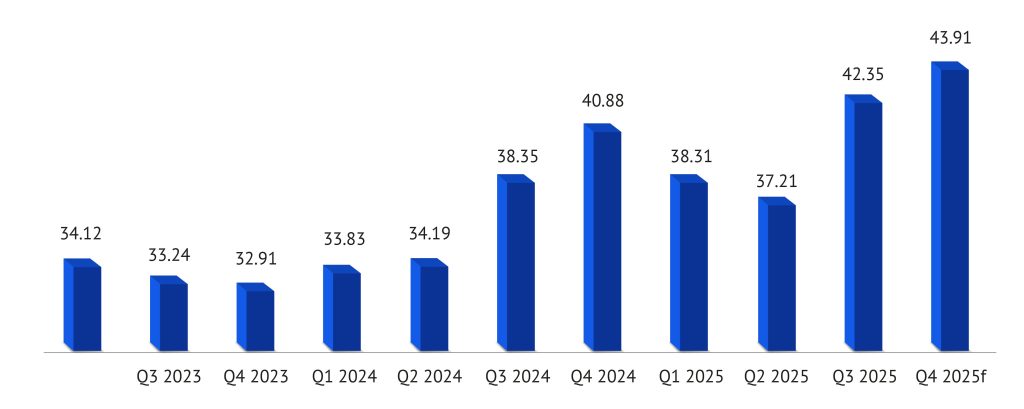

Figure 1: Gross External Reserves ($’ Billion)

Source: NBS, Agusto & Co. Research

On the fiscal front, the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms undertook a landmark attempt to simplify Nigeria’s notoriously complex tax environment (from over 60 distinct taxes to just eight) aiming to expand the non-oil revenue base and reduce reliance on volatile oil rents. Parallel reforms in the power sector through the 2024 Electricity Act dismantled the federal grid monopoly, empowering states to regulate and issue independent electricity licences. These reforms, coupled with the phased removal of subsidies for heavy electricity users, ushered in critical moves towards cost-reflective tariffs despite political sensitivities

Tangible Gains vs. Deep Scars

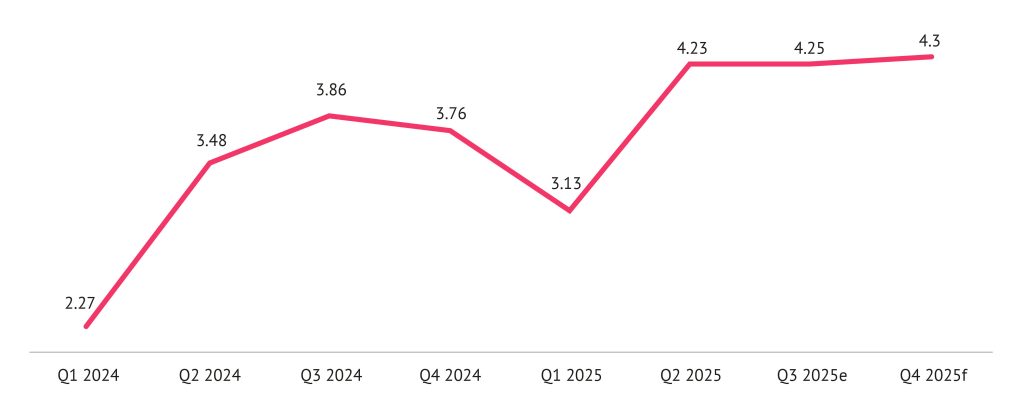

Viewed from a purely macro-perspective, this multi-pronged reform package is beginning to yield “green shoots” of stability. Nigeria’s GDP growth accelerated to 3.13% in Q1 2025 and 4.23% in Q2 2025 – fastest pace since 2021. Critically, this was fuelled by a resurgent oil sector, which rose by over 20% in Q2 2025 as production finally climbed to 1.68 million barrels per day (mbpd) – the highest since 2020 – compared to 1.41 mbpd recorded in Q2 2024.

Figure 2: Real GDP Growth (%)

Source: NBS, Agusto & Co. Research

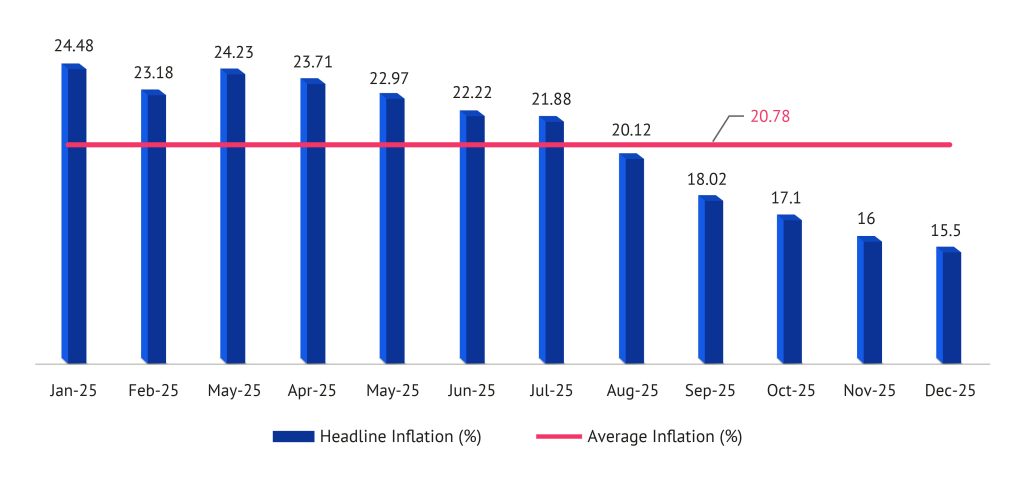

This oil-led recovery, combined with the FX reforms, has stabilised government revenues and boosted foreign reserves, which recovered from a low of $32.9 billion at the end of 2023 to over $42.86 billion by October 2025. Crucially, the CBN’s return to monetary policy orthodox has contributed significantly to headline inflation moving onto a clear disinflationary path, easing from its December 2024 peak to 18.02% by September 2025, aided in part by a statistical rebasing of the Consumer Price Index, and improved foreign exchange liquidity.

Figure 3: Headline Inflation (%)

Source: NBS

This renewed policy clarity and high-yield environment were successful in its primary objective: attracting portfolio capital. The NBS capital importation data for Q1 2025, for instance, showed a 67% year-on-year jump, to $5.64 billion, overwhelmingly driven by Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI) into high-yield government debt (74.6% of total capital imported). In our assessment, this influx of “hot money” was the primary factor in arresting the Naira’s freefall and establishing a new, stable floor in the ₦1450-₦1500/$ range.

Capital Gains Tax and Exchange Rate Stability

However, this hard-won stability is both fragile and, in our view, now directly threatened by a new policy friction. FPI inflows, which the CBN has worked to attract, are highly sensitive to new taxes. The fiscal reform committee’s proposal to reintroduce Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on securities transactions, effectively removing a long-standing exemption for stocks and bonds, creates a direct policy conflict. The “pull” factor of high-interest rates is now being countered by the “push” factor of a new tax, which could be as high as 30%. This introduces a direct fiscal disincentive, possibly jeopardising Nigeria’s appeal as an investment destination – a shift that could prompt profit-taking ahead of implementation deadlines, disrupting liquidity and dampening market sentiment.

Though exemptions exist for proceeds reinvested within Nigerian markets, which aim to encourage long-term capital retention, we believe that the immediate perception of higher taxes will likely reduce overall foreign participation, which risks renewed currency volatility, depreciated reserves, and weakening macroeconomic gains.

Figure 5: FDI Vs FPI ($’ million)

Source: NBS

The FPI surge masks a worrying collapse in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) – the “patient” capital crucial for driving tangible growth and creating jobs. FDI inflows were $126.29 million in Q1 2025, a marginal 5.97% higher than the $119.18 million recorded in Q1 2024, but reflecting a 70% plunge from $421.88 million in Q4 2024. However, the share of FDI in total capital importation declined a paltry 2.24% in Q1 2025 – a steep drop from 8.29% in Q4 2024 and even lower than the 3.53% recorded in Q1 2024. This signals that while “hot money” is willing to bet on Nigeria’s yields, long-term investors remain terrified by the operating environment.

Microeconomic Disconnect: The Real Economy’s Struggle

This disconnect between the macro picture and the micro-reality being the central crisis of the reform agenda. The anticipated “trickle-down” effect has been largely unrealised as the reforms collided with a low-productivity, high-cost economy, resulting in real wages remaining depressed, and aggregate demand is crushed under the weight of inflation. This wage-price disconnect has annihilated aggregate demand being crushed, constraining the non-oil economy, which relies on consumer spending. The official unemployment rate, a seemingly benign 4.3% in Q2 2024, is a statistical illusion. The NBS’s new methodology captures a reality where, by its own data, 93% of workers are in the informal sector and 85.6% are “self-employed.” These are not salaried workers, but rather individuals largely subsisting in low-productivity roles that cannot fuel wage increases or expanded domestic consumption.

Looking Ahead: From Stability to Inclusive Growth

In summary, Nigeria’s reform agenda has achieved a tentative macroeconomic reset. Yet, it is a fragile equilibrium, largely purchased at the population’s expense through compressed living standards. However, this stability is merely the prerequisite for growth, not the destination. To convert this stability into strength and finally deliver tangible benefits to the populace, the focus must shift from monetary stabilisation to tackling the binding constraints on productivity.

Security remains a paramount economic concern. Endemic insecurity in food-producing regions acts as a 20-30% “unofficial tax” on food, as logistics firms pay for armed escorts. This structurally anchors food inflation, undermining the CBN’s efforts. Until farms are secure and transit routes are safe, food prices will not fall, real wages will not recover, and aggregate demand will remain crippled. Second is the execution of the power sector reforms. The Electricity Act’s decentralisation is a brilliant policy, but it must be implemented with urgency to lower costs for the productive MSME sector. Third is the need for fiscal execution and policy alignment. The tax committee’s reforms to simplify the tax code are essential, but they must be implemented in a way that does not conflict with monetary policy. Scaring off the portfolio capital that anchors the currency, before FDI has returned, is a risk Nigeria cannot afford.

In conclusion, the verdict on Nigeria’s reforms is starkly mixed. The administration has bought itself a foundation of stability with the population’s purchasing power. The only way to repay that cost is to now, ensure its next policy steps decisively prioritise productive, inclusive, and sustainable growth.